Hi and welcome to the first post for a shiny new newsletter section, Cool Book Facts! 📚😎

What this is: Once a month I’ll bring you a dive into some of the amazing things I have uncovered over the course of my research for writing books. COOL things. Could be a cool piece of research or history or an event.

Why you are subscribed: because you subscribe to my author newsletter. But listen, if you do not want cool book facts, that’s okay! Really! I won’t pretend to understand it, but I will respect it. Our inboxes are cluttered as it is. You can unsubscribe any time.

What to do now: Read on! Today I’m talking about the SUPER COOL, bluest-of-blue Ishtar Gate! You’re going to be a fan by the end.

Welcome to Babylon

Picture this: you’re riding up a dusty, hot road, covered in layers of sweat and splatters of horse dung. You’re tired and thirsty and your horse, Clarence, has developed a narky attitude in the last hour. He tried to bite you and you’re trying to decide whether to have a long-overdue talk with him later.

It’s also the year 576 BC.

Your own spirits are flagging and you just, for the love of the Babylonian god Marduk, want to lie down and eat something that isn’t coated in sand.

But then you see a glimpse of soul-piercing blue glazed tiles, shining in the sun.

You forget about telling off Clarence. You have GOT to see that gate and those walls!

King Nebuchadnezzar II, who reigned in Babylon from 604-562 BCE, said, “I’mma build walls and a gate and dedicate them to gods and goddesses, and it’s gonna be lit AF.” (Exact quote!)

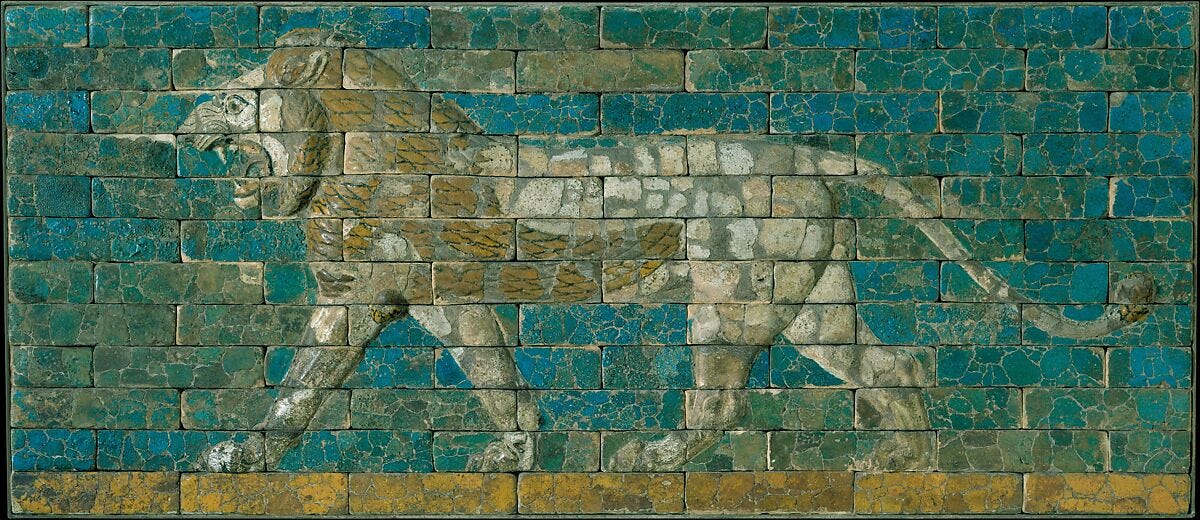

The resulting Ishtar Gate was a symbol of splendor and beauty, built of blue-glazed, sun-baked bricks intended to mimic lapis lazuli. The processional way leading to this stunning gate was studded with reliefs of aurochs, dragons, and bulls with delicate flowers as a border.

Curled along the often-changing Euphrates River (it has changed its course several times over hundreds of years), Babylon was the center of culture and politics of Babylonia. The first Babylonian Empire extends back to the 17th century BC, established by the Amorite king Hammurabi (of Code of Hammurabi fame, which is still taught to school children today—at least my kids got this).

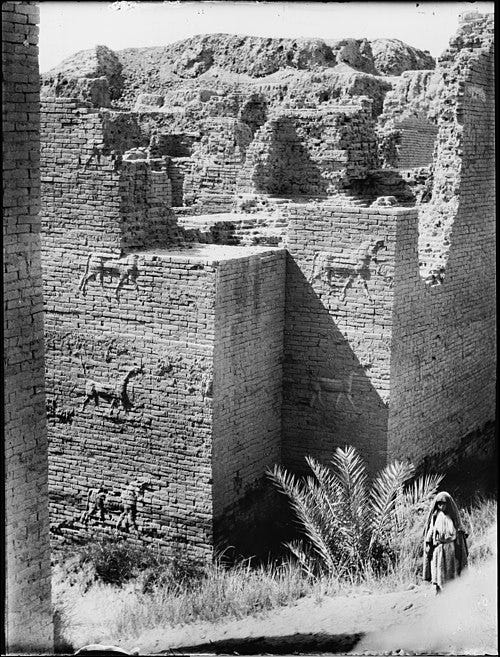

The basic walls of the city, processional way, and Ishtar Gate were built of unbaked mud brick with foundations that are quite deep into the ground. The walls and gates were rebuilt numerous times, with “nine layers of unglazed relief animals” documented. All of these would face visitors to protect the city from evils.

Gold and brown glazes were used for animal panels on the Processional Way.

Today, Babylon is the city of Hillah in Iraq.

And the Ishtar Gate? With its stunning, bluer-than-blue tiles? You can see it today…in Berlin, Germany.

New gate, who dis?

Usually an earthquake topples monuments of antiquity, but the gate and walls here were probably buried by shifting political climes and time. Whatever it was, in the late 1800s, the British began excavation on Babylonian walls and palaces and then from 1904-1914 German archaeologist Robert Koldewey began a deep excavation and uncovered the Ishtar Gate.

(Koldeway’s Wikipedia page also says he uncovered the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the seven ancient wonders of the world, but this is patently false. No one has found them. They might not have existed at all. You’ll be hearing more from me on this subject in the future.)

Anyway, Koldewey’s German team, along with French and British teams, smuggled a bunch of things out of the site to justify the costs of the excavation, which is an astonishing little line, isn’t it? That’s like saying I can walk into a bank and take thousands of unmarked bills to justify my walk downtown. This perfidy was facilitated by Iraq being a British protectorate between the world wars, during which Britain also helped themselves to several Babylonian treasures, all of which now live in the British Museum (but then, what doesn’t?).

Turns out, the Germans smuggled the entire Ishtar Gate, along with most of the friezes from the Processional Way (out of 120 friezes, the Germans took 118; makes you wonder whether the remaining 2 were damaged or ugly), packed in coal barrels and then shucked down the Euphrates River where they were smoothly loaded onto German ships that happened to be waiting.

“What? We were just sitting here! Someone shoved these crates on! We don’t know what you’re talking about!” - the crew of the German ships, probably.

The Germans were quite pleased with themselves in this endeavor, carefully marking each tile for later rebuild.

“This rebuild based on our complex and careful numbering of tiles in Berlin is gonna SLAP,” they said. (Exact quote.)

Once in Berlin, the Ishtar Gate was painstakingly desalinated, reconstructed, and installed in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum, where the gate remains a major attraction today. Many bottles of Champagne were probably popped in celebration of their hard work at removing this gate and rebuilding it in Germany.

Iraq isn’t thrilled about this situation.

The Ishtar Gate is frequently brought up in art repatriation discussions. Iraq has tried twice to get it back and Germany has both times said, “The number you are trying to reach is no longer in service.” And also, “Besides which, we have a law in Germany saying it was fine to take it. We made that law recently, but it still stands.” (Exact quotes.)

An argument could be made that, given Hillah’s location in Iraq as a major center of fighting—the United States began there with heavy fighting when they invaded Iraq in 2003—that the Ishtar Gate should remain in Berlin, where it is safer. Additionally, terrorist organizations throughout the Middle East frequently destroy or raid pieces of antiquity to fund their operations; it is a major source of their income.

But surely Germany could also apologize and develop a reciprocal program? As difficult as moving the gate would be? No? Just an apology then? (There have been no apologies.)

Perhaps impatiently, Saddam Hussein had a little replica built of the gate in Hillah in the 1960s. It’s…not great. It looks like an amusement park entrance.

What do you think?

Hey, what about those Processional Way animal panels?

You might be able to see some of these beauties because they were split up and distributed around the world so that everyone but Iraq, I guess, can enjoy the splendor.

The Istanbul Archaeology Museum - lions, dragons, and bulls

The Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen, Denmark - one lion, one dragon, and one bull

The Detroit Institute of Arts in Detroit, Michigan - dragon panel, but I wasn’t able to find a catalog entry

The Röhsska Museum in Gothenburg, Sweden - one dragon and one lion

The Louvre - lion

The State Museum of Egyptian Art in Munich - lion

The Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna - lion

The Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto - lion

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York - lion, not currently on display, which is dumb

The Oriental Institute in Chicago - lion

The Rhode Island School of Design Museum - lion

The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston - lion

The Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut - lion

You should go see one. If you HAVE seen one, please let me know! And if you live in a city with one, demand to see it. “Go get it out of storage RIGHT NOW,” you could say.

Why I wrote this post

The magnificent Ishtar Gate is but one of the amazing things I’ve come across in research for my next book. It is so beautiful and also interesting in a repatriation-discussion-way.

There is lots to think about here with the morality of taking these gorgeous things from their original locations, the spreading of them around the world, and the ignoring of pleas to return. But also, you can still see this ancient gate and that’s no small thing these days.

Sources

This was fascinating, Sierra! Thanks for the post!

Wonderful story! The gate is beautiful! Yassou! Koukla mou!!!